BY Wendy Perkins

Photography by Tammy Spratt

Perched on a south-facing hillside of the San Diego Zoo Safari Park is a community of unusual and highly specialized plants that make up the Old World Garden. Against a canvas of earth the color of a lightly baked biscuit, a botanical smorgasboard from the other side of the Atlantic creates a scene like no other. Some are tall, others grow low or sprawl. Carefully curated and placed for the plant’s well-being as well as visual interest, the garden is eyecatching. Yet, like any work of art, the individual elements are as worthy of notice as the overall scene. The Old World Garden has some odd, yet fascinating details of interest.

Handle with Care

A great majority of the plants in this gardenscape are succulents from Africa, Madagascar, and the Arabian Peninsula. The aloe group is well-represented, as is the genus Euphorbia. The latter genus contains about 2,000 species, making it one of the largest in the Plant Kingdom. This group of plants was named by King Juba of Mauritania after his physician, Euphorbus, who reportedly used the latex sap from one species in his medicinal potions. It’s interesting that King Juba lived long enough to coin the name after following doctor’s orders—the sap is poisonous if swallowed, and it can cause irritation and blistering if it comes in contact with skin!

Succulent Shapes

Adapted to many different niches, euphorbias in the Old World Garden give a good idea of the range of shapes and sizes that various species display. The Latin word euphorbus means “well fed,” and the description does fit the fat, succulent appearance of many members of the genus. A mature candelabra tree Euphorbia ingens may have a trunk diameter of two feet.

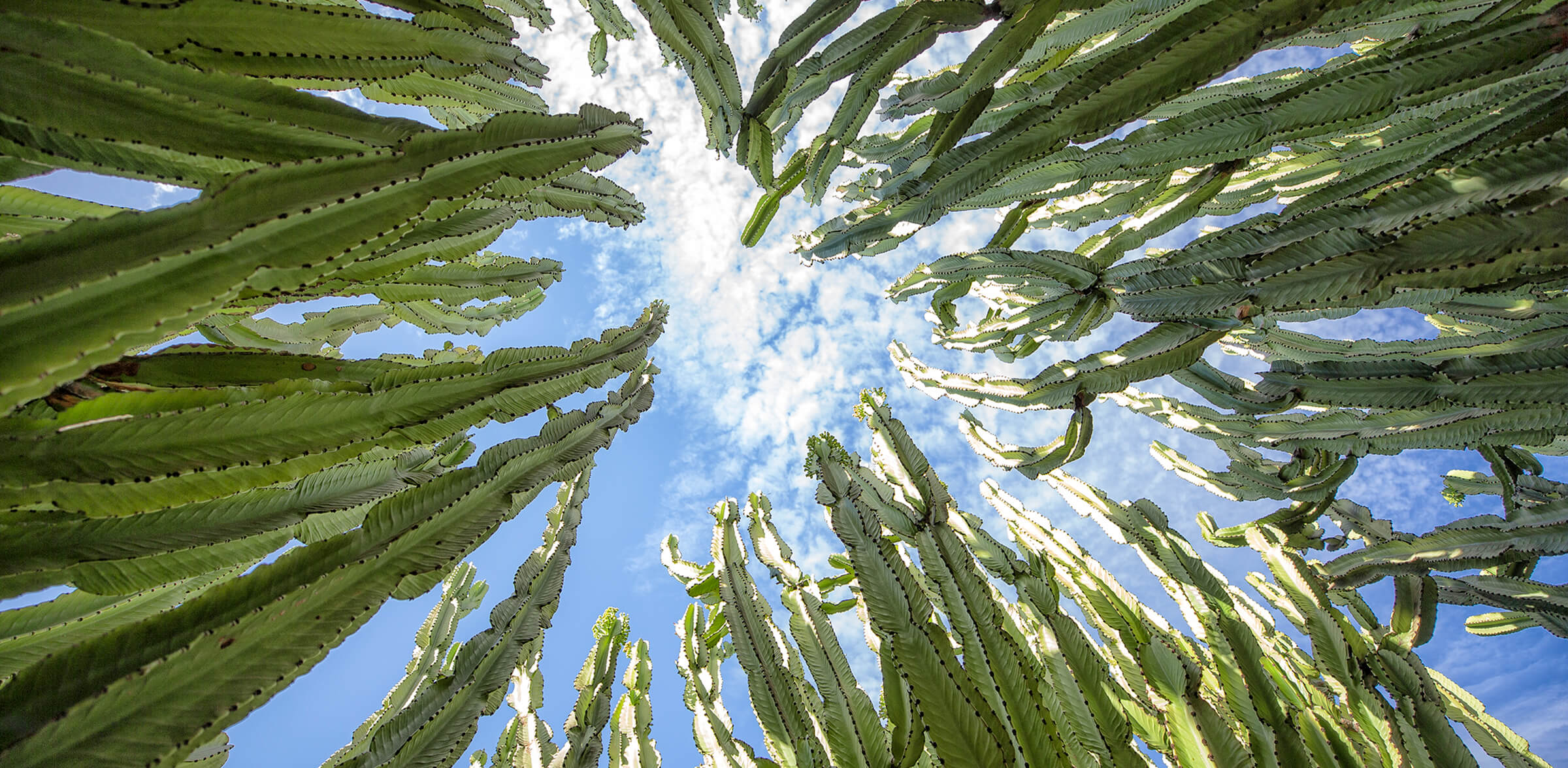

CLOSE, BUT NO CACTUS

Left: As seen here, thorns on E. ingens grow from the stem edges—unlike the spines of a cactus, which grow from a fuzzy spot called an areole. Right: The silhouette of its upright branches earned E. ingens the common name candelabra tree.

Native to southern Africa, candelabra trees can reach heights of 30 to 40 feet. At that size, they look a bit like a giant lollipop: a bare trunk topped by a round-shaped cluster of branches. When they’re younger, however, the plants do indeed look more like candelabras—albeit intricately twisted ones. The candelabra tree in the Old World Garden shows this fascinating form well. Across the E. ingens range, people plant them close to one another. As the plants’ arms grow and intertwine, they form a sort of living fence. The sharp thorns are enough to stop most animals; but if one plows through, it’s in for a surprise—breaking a branch unleashes a flow of stinging sap!

TAKING SHAPE

Succulent growers have achieved some fun and fascinating results creating hybrids of E. caput-medusae (top left). Some variations seem to resemble marine animals, like a sea star (top right), octopus (lower center), and even a sea urchin (lower left and right).

Reaching Out

Near the tall candelabra tree at the Safari Park, another euphorbia takes things to a whole new level—down low. The multiple, snakelike branches of the aptly named Medusa’s head E. caput-medusae grow from a central point, reaching, twisting, and sprawling. The long, bumpy stems even have the scaly look of a snake; it’s no wonder the plant’s common name draws on the appearance of the mythical snake-haired monster.

Bumps Ahead

The corn cob plant E. mammillaris, another low-growing member of the genus, also gets its common name from its appearance: plump bumps on the branches look like kernels of corn. The short but deeply ribbed stems grow in dense clusters, which helps ease the brunt of the searing heat in its native habitat of the Cape Province in South Africa.

Octopus Plants

The human habit of bestowing a common name based on a plant’s appearance is fun, but it can also cause a bit of confusion. For example, two very different plants in the Old World Garden are known as octopus trees. To complicate matters further, they each have other common names, and they have distinct taxonomic labels.

MAKE WAY

Horizontally growing young stems of a zig zag plant stake out a no-grow zone for most other plants, giving it less competition for precious water.

In the Old World Garden, one “octopus” is better known as the zig zag plant Didera trolii. Juvenile plants are a jumble of ground-hugging, spiny stems that do, indeed, go this way and that. Spreading out from the point of origin, the branches have soon laid claim to a good chunk of real estate. As the plant matures, it produces upright stems as well, taking advantage of open space in the vertical dimension.

LOOK ALIKES

Although the Madagascar ocotillo Alluadia procera looks like and has adaptations similar to the ocotillo (genus Fouquieria) of southwestern US and Mexico, the two plants are not related.

The other “octopus” is generally known as the Madagascar ocotillo Alluadia procera. This alien-looking plant is native to southern Madagascar, a region that sometimes gets no rainfall for a year or more. During severe droughts, this plant drops its leaves to conserve moisture. Let the rain come, however, and A. procera can sprout new leaves within a day or so. This tough survivor is a significant component of Madagascar’s spiny desert habitat, where the zig zag plant also lives.

Bottled Water

The Madagascar bottle tree Pachypodium lamerei (seen above), with its thorn-studded trunk and a bouffant of leaves and flowers on top, has its own approach to getting through the dry times. The term “bottle tree” reflects both the form and function of the plant’s trunk. Like euphorbias, Pachypodium are stem succulents, holding water in their fleshy stems. As the tree ages, its trunk grows thicker and thicker as moisture is stored.

Live Small, Smell Large

Another stem succulent in the Old World Garden doesn’t stand out much—until it flowers. Known to botanists and horticulturists as Stapelia, layfolk know them as carrion flowers. And you can probably guess how they got that name! For most of the year, a Stapelia is simply a cluster of eight-inch-tall, deeply ribbed stems. They look a bit like fingers reaching up from below the ground. When they bloom, the amazing, star-shaped flowers are surprisingly large—up to 14 inches wide—and have an odor some people find offensive. It’s said that the scent is somewhere between a ripe garbage can and decaying animal flesh. Yet, that’s the perfect lure for this plant’s prime pollinator: flies.

Looking Rosy

The stop-you-in-your-tracks, brilliant blossoms of Addenium obesum (above) were likely the reason it became commonly known as the desert rose, even though it is in the dogbane family. Perhaps an intense hue such as this was not expected among succulent plants of the Sahel region of Africa. Yet, there it is. Desert rose plants (also known as mock azalea and impala lily) survive their harsh climate by holding moisture in their thickened trunk, called a caudex, and in their stems. They grow slowly, taking on a short, squat shape to store water. Desert rose plants are becoming better known and appreciated as a houseplant (warning: they cannot withstand freezing temperatures, however). Blooming from winter to spring, they can help brighten winter days as indoor houseplants in chilly climes. At the Safari Park, though, they live and thrive outside, surrounded by the eager eyes of guests discovering the treasures of our Old World Garden.