BY Peggy Scott

Photography by Ken Bohn

When “monster” is part of your given name, the opinion others have of you is pretty clear. So fearsome was the largely erroneous legend of the Gila monster Heloderma suspectum that Old West tall tales warned of the deadliness of even the mere breath expelled by the creature. But remember the adage about believing what you hear? Michael Garr, wildlife care specialist in the Zoo’s Department of Herpetology and Ichthyology, would like people to take it to heart when considering this misunderstood monster. “Gila monsters tend to be slow, lumbering lizards that are often non-aggressive,” Michael says, adding that stories of the monsters’ ferocity are overblown. It often isn’t easy to separate fact from fiction, but in this case, it’s only fair.

Of Monsters and Myths

A venomous lizard species, the Gila monster lives in the deserts of northwestern Mexico and parts of California, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, and Arizona. The name Gila refers to the Gila River Basin in Arizona, where the monster was once plentiful.

There seem to be as many myths as there are actual Gila monsters. Along with the toxic-breath belief, locals once swore that should a Gila monster bite down, it wouldn’t let go until the sky thundered or the sun set. The animal also possesses, according to lore, the ability to spit venom, sting with its tongue, and, Michael notes, jump “higher and farther than any frog in the world.” One other legend is physiologically perplexing: “Why is the Gila monster venomous? Because it lacks an anus, and all that stuff went bad in there.” And, most amazingly, according to the plot of the 1959 B-movie The Giant Gila Monster, this incredible creature can grow to the size of a bus and wreak havoc on small Texas towns, chomping down hot-rodders. Even the Gila monster itself didn’t want to be in this cinematic masterpiece, as the title character was actually played by a Mexican beaded lizard!

Hollywood’s creative license aside, in reality there isn’t need for such fantasy when the real story is much more interesting.

Skin Deep—and Then Some

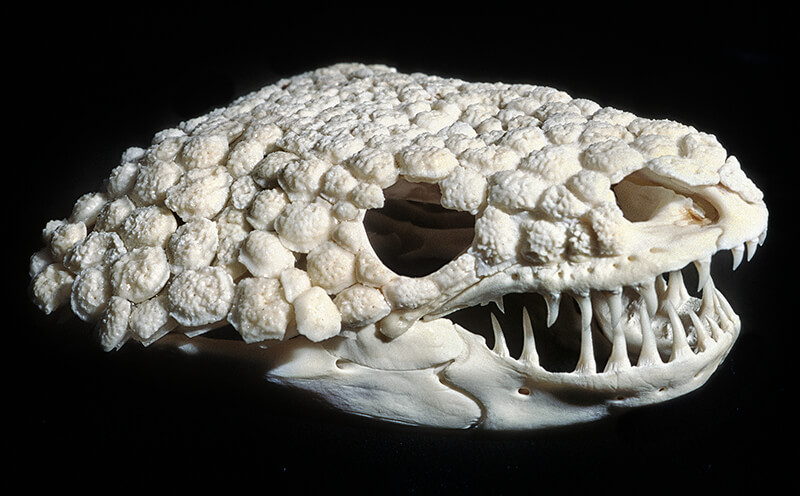

A large, heavy-bodied lizard, the Gila monster measures up to two feet in length and weighs as much as three pounds. Males are larger and bulkier than females and have a broader head. The skin is orange, pink, or yellow and black, usually in a reticulated pattern, but in a banded pattern in some populations. Heloderma means studded or warty skin, likely referring to the beaded look of the animal’s dorsal scales, which is due to the presence of osteoderms (small bones) under the scales. This makes the skin harder to penetrate and helps protect the lizard, and the bumpy surface isn’t just skin deep. The surface of the Gila monster’s skull isn’t smooth like most skulls. It has little bumps all over it that act like built-in armor.

A PHRENOLOGIST’S DREAM

The bumps on a Gila monster’s skull may not predict their personality traits, but they do protect the head—like built-in armor.

Equally impressive is the monster’s bite and venom-delivery system. Venom is produced in glands in the lower jaw, but it is not injected through fangs the way snakes do it. Rather, each of the lizard’s lower teeth is deeply grooved and flanked by a cutting edge that punctures the prey’s skin. When the lizard bites and begins to chew, venom flows into the wound from between the lower lips and teeth through capillary action. The venom kills tissue, and gets in the blood system. The effects include severe pain, a drop in blood pressure, and respiratory failure, but a Gila monster bite is rarely fatal to humans—if a bite occurs at all. “These lizards do not chase down prey, let alone people,” Michael says. An antivenom isn’t even made because fatalities are so rare.

Daily Lizard Life

Gila monsters prey on newborn rodents, rabbits, and hares, though they won’t say no to a meal of nesting birds or other lizards and their eggs. Prey may be crushed to death if large or eaten alive if small, swallowed head first and helped down by muscular throat contractions and neck flexing. And while a Gila monster can eat one third of its body mass in one “sitting,” it doesn’t dine very often, only 5 to 10 times per year in the wild.

Strong diggers, Gila monsters spend most of their time underground in burrows, where they might find a cool, comfortable spot. Even though they live in deserts, Gila monsters don’t really like the heat. Researchers have inserted data loggers down into Gila monster burrows, and the highest temperature recorded was 78 degrees Fahrenheit (25.6 Celcius).

Because of the myths and perceived danger associated with them, Gila monsters were often killed on sight. In 1952, the Gila monster became the first venomous animal in North America to be afforded legal protection, making it illegal to collect, kill, or sell them in Arizona. While people are not allowed to take Gila monsters from the wild, offspring from captive lizards are sold in the pet trade. Laws vary, and specific permits are required for native species and venomous species within each state. And it’s often hard to prove individual lizards were captive-bred.

Meet the Monsters

Five Gila monsters currently live at the San Diego Zoo—two can be seen at the Zoo’s Reptile House. Wildlife care specialists at the Zoo note they can be tricky to manage since they live so long—some of the ones residing here now were confiscated from illegal sales back in 1981. They can live well beyond 40 years.

The specialists who care for these beautiful animals every day have at least some company in believing these animals have been wrongly accused. As Dr. Ward, a physician, wrote in the Arizona Graphic in September 1899: “I have never been called to attend a case of Gila monster bite, and I don’t want to be. I think a man who is fool enough to get bitten by a Gila monster ought to die. The creature is so sluggish and slow of movement that the victim of its bite is compelled to help largely in order to get bitten.” Now that’s a biting commentary.

(Top photo by: reptiles4all/iStock / Getty Images Plus)