And Then There Were Two

San Diego Zoo Global supports and contributes to boots-on-the-ground, anti-poaching efforts in Africa.

BY Karyl Carmignani

Photography by Ken Bohn

She ambles across the dusty landscape, sun beating down on her furrowed back. Her daughter Fatu, now 18 years old, joins her, and their horns gently brush in greeting. Dark eyes take in the pair of armed guards—friends, really—who hover nearby protecting them at Ol Pejeta Conservancy in Kenya. While Najin’s big, burly, barrel-shaped body cannot shield them from poachers’ bullets, the courageous guards surely will. Side by side, the rhinos’ wide-lipped mouths daintily mow all things green along the ground: they are grass-powered and mighty. Since beloved Sudan, Najin’s 45-year-old father, passed away last March from age-related health issues, this duo is the last of their kind on the planet.

THE CRASH

It is hoped that the group of southern white rhinos at the Safari Park will reproduce and eventually be surrogate mothers to northern white rhino calves.

How Did We Get Here?

Unrelenting poaching—driven by greed and corruption, outdated cultural beliefs, and little mercy—is marching all five rhino species toward annihilation. Killing a two-ton animal for its five-pound horn, to be crushed into dust and consumed as a folk remedy or flaunted as a status symbol, is morally reprehensible. Yet it happens every single day. Surviving for millions of years, the northern subspecies of the white rhino, Ceratotherium simum cottoni now stands, stubby horns held high, on the precipice of certain extinction.

The northern white rhino once ranged over parts of Uganda, Chad, Sudan, the Central African Republic, and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), formerly Zaire. In the 1960s, there were about 2,360 northern white rhinos, but civil war and persistent poaching reduced them to a single population of about 15 animals at the Garamba National Park in northeastern DRC. As war raged and ebbed around them, a courageous woman, Kes Hillman-Smith, Ph.D., coordinated conservation and protection efforts in the park for over 20 years, and gradually coaxed the northern white population up to 35 animals. In 2004, the first wave of poachers entered the park. Hillman-Smith told The Telegraph newspaper of London at the time, “Unless there is a major level of support, we are going to lose the last population of northern white rhinos.”

Sadly, she was correct.

FACING THE FUTURE

While rhinos still face rampant poaching in the wild, it is hoped that humans will find alternatives to using rhino horn for folk remedies and status symbols. You can help save rhinos by supporting our conservation efforts at endextinction.org, visiting the San Diego Zoo and Safari Park, and learning more about these incredible, ancient animals.

The backup plan was to breed northern white rhinos in zoos and parks, creating an assurance population beyond the reach of poachers and war. Twenty-two northern white rhinos were collected from Africa for this effort between 1948 and the mid 1970s. Despite efforts to breed them at Dvůr Králové Zoo in the Czech Republic and at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park, only one female, Nasima, reproduced. It was hoped that Angalifu and Nola would breed at the Safari Park, but they never hit it off. Both rhinos became elderly; Angalifu passed away in December 2014 and Nola died in November 2015. One of Nasima’s offspring, Najin, is the only female with next-generation bragging rights: she gave birth in 2000 to Fatu, the last northern white rhino ever born.

In 2009, the final four fertile animals—two males and two females—were moved from the Czech Republic back to Africa in a last-ditch breeding effort. To ward off poachers, the 4 rhinos were under 24-hour armed surveillance at Ol Pejeta Conservancy in Kenya. Suni, a male, died in 2014, followed by the other male, Sudan, in 2018, without producing offspring. Najin and her daughter are infertile.

COMPLETE COOPERATION

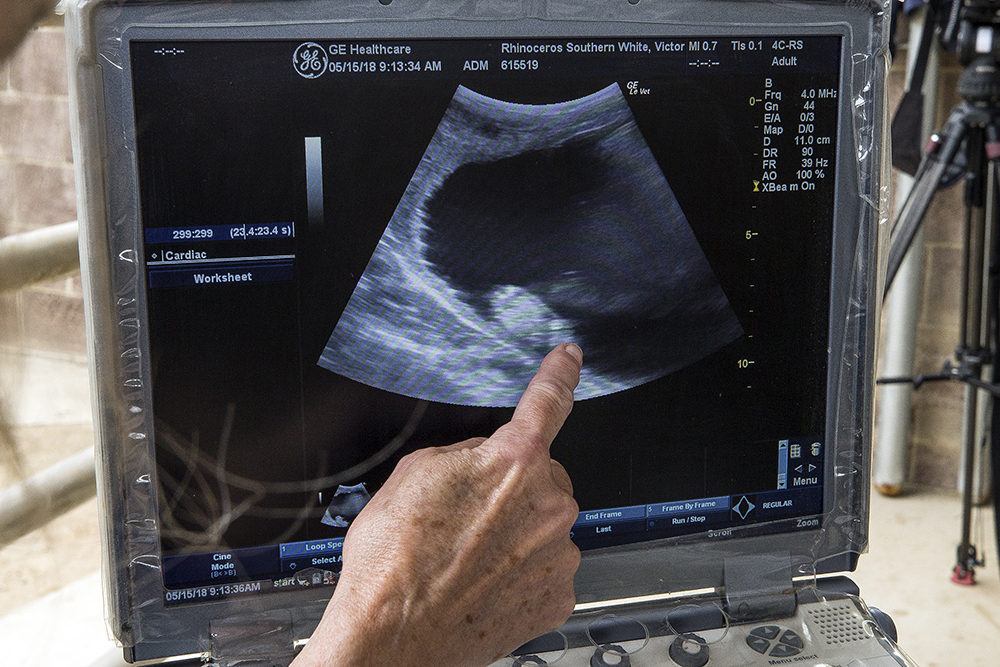

Dr. Barbara Durrant (right) and Parker Pennington, Ph.D. conduct a transrectal ultrasound scan on a southern white rhino, who remains relaxed throughout the procedure. Scientists are learning a great deal about rhino reproduction, which will benefit the northern white rhino and other critically endangered species.

Where Are We Headed?

It’s a cool, overcast morning, and Nikita and Amani are still snuggled up in the barn at the 3.5-acre Nikita Kahn Rhino Rescue Center at the Safari Park. Barbara Durrant, Ph.D., director of Reproductive Sciences, and Parker Pennington, Ph.D., postdoctoral associate, haul out the required gear to conduct a transrectal ultrasound scan on two southern white rhinos. “We could not do any of this rhino work without the keepers,” said Barbara. “They have trained the animals through positive reinforcement and have built up trust. They know the nuances of each animal.” All of that comes into play when getting an animal that weighs as much as an SUV to saunter into a chute and remain still for 20 to 30 minutes, while the scientists observe and document her complex reproductive tract with an ultrasound probe. It’s a long reach, requiring shoulder-length gloves, since a rhino’s ovaries are nearly four feet deep inside her abdomen.

ULTRA SOUND SCIENCE

Scientists are learning a great deal about the complexities within the rhinos’ reproductive tract. Ultrasounds help them observe and document changes like follicle growth and embryo development within the uterus.

The exam is part art form, part rapt concentration, as researchers do not want to damage the membrane surrounding the passageway. Keepers manage the front end of the rhino, feeding her fruits, vegetables, and hay while talking to her. If there is any indication of discomfort, or she seems unsettled, they immediately discontinue the procedure. “It’s all voluntary,” said Barbara. “Animal welfare is our top priority.”

In November 2015, six southern white rhinos arrived at the Safari Park from private reserves in South Africa. Locals were grateful the animals were being relocated, as the people simply cannot protect them from poachers marauding in the vast wildlife reserves. The Rhino Rescue Center was built at the Safari Park expressly to home these rhinos for this science-based conservation project. The goal is to develop and perfect assisted reproductive technologies to enable southern white rhinos to serve as surrogate mothers for the northern white rhino, and eventually lead to a self-sustaining population of northern whites.

PATIENCE AND PASSION

Safari Park keepers work patiently with the rhinos to form trust and train them to participate in health care procedures. It is based entirely on positive reinforcement. The rhinos seem quite agreeable to this arrangement!

It’s a complicated endeavor, as little is known about white rhino ovarian dynamics, ovulation cycles (females randomly toggle between 30- and 70-day cycles), and follicle growth. Currently, artificial insemination (AI) techniques are being worked out, hence the weekly ultrasound scans to monitor ovulation and follicle development in each animal. Last May, early pregnancy was detected in Victoria, making her the first rhino in our history to become pregnant through artificial insemination.

MOVING FORWARD

Scientists from an array of different fields are collaborating to save the northern white rhino. The crash of southern white rhinos at the Safari Park seems eager to do their part.

Through this detailed study, “This work will generate knowledge to aid in the conservation of this species and many others,” said Barbara. The AI process is first being tried to produce southern white rhino calves. They will be a huge boost to the North American zoo population, which is not currently self-sustaining due to limited reproduction. Eventually, the hope is that all six female southern white rhinos—Amani, Helena, Livia, Nikita, Victoria, and Wallis—will become surrogate moms for northern white rhino calves, through assisted reproduction (embryo transfer).

At about 10 years old, Amani was the first for AI—and also San Diego Zoo Global’s first attempt to artificially inseminate a rhino. While neither of those two procedures resulted in a pregnancy, it was a tremendous learning experience for the team, improving the chances of success in the near future, as Victoria’s pregnancy attests. Amani may breed naturally with Maoto (the Park’s southern white rhino bull), and if succeessful, her first pregnancy will grease the wheels for later reproduction.

RAIN OR SHINE

Nikita’s keeper uses a whistle to “bridge” desirable behaviors, like following a hand signal, and the rhino gets a tasty a reward for a job well done.

The Future is Now

In 1979, the first northern white rhino genetic material was added to San Diego Zoo Global’s Frozen Zoo®. “It was an exercise in taking the long view,” observed Oliver Ryder, Ph.D., director of Conservation Genetics at the San Diego Zoo Institute for Conservation Research. “The Frozen Zoo started when today’s technology was beyond reasonable imagination. Yet we had confidence that these materials would be productive and used to help save species.” There are viable cell cultures from 12 northern white rhinos cryopreserved in the Frozen Zoo, and their genome sequences reveal “sufficient variations to save this subspecies.”

The southern white rhino underwent a genetic bottleneck (down to about 40 animals), and took until 2012 to rebound to 20,000 animals; the northern whites declined even more precipitously. But the genetic diversity in even 12 cell lines could rescue this subspecies. It will require long-term, multidisciplinary science, including expertise from animal care staff, behavioral biology, genetics, reproductive physiology, endocrinology, disease management, and nutrition.

A RHINO CRASH

Four of the six female southern white rhinos brought to the Safari Park in 2015 to help resurrect the northern white rhino.

The simplest way to begin to generate a northern white rhino offspring is to fertilize an ovum (egg cell) with sperm—but unfortunately ova from northern white rhinos have not been preserved. However, there is preserved ovarian tissue that may contain stem cells and immature ova; plus, our ability to reprogram skin cells into stem cells and produce functional sperm and eggs is improving rapidly. Barbara noted that “other reproductive possibilities on our radar include creating a hybrid between the southern white rhino and the northern white rhino, or cloning the animal,” if that’s feasible with this species. The only certainty is that resurrecting the northern white rhino will involve stem cell resources. “We are realistic, yet confident that what we’re trying to do here can change the future of conservation,” said Oliver. “The optimistic intention of the Frozen Zoo is now showing potential.”

VICTORIA’S VICTORY

For the first time in San Diego Zoo Global’s history, artificial insemination has resulted in a pregnancy for southern white rhino, Victoria. It is a critical milestone in the ongoing work to develop the scientific knowledge required to genetically recover the northern white rhino. Congratulations!

Ethics and Extinction

Bringing an extinct animal back is not without its thorny ethical issues. Some say we should just “let things play out, as extinction is natural.” Discussion of bringing back an animal like the woolly mammoth, while popular in the media, is problematic for several reasons, including that it went extinct 10,000 years ago, and its habitat no longer exists. The northern white rhino, however, has been decimated very recently by humans, and its habitat is still relatively plentiful within its range. Many feel we have a moral obligation to save species our actions caused to decline.

This project is developing “a tool kit for when the wild is a safe place to put them back,” said Parker, “and these techniques and protocols could benefit other species as well.” By the time a northern white rhino calf is on the ground, it is hoped that the poaching epidemic will have receded.

San Diego Zoo Global is committed to leading the fight against extinction. With our partners and a multidisciplinary approach, we are optimistic that one day we will have a northern white rhino calf trotting beside its southern white rhino mother. Being good stewards of the Earth isn’t easy, but it is necessary. “We recognize we’re playing a role that shapes the future of biodiversity,” said Oliver. “We have a stewardship obligation to explore the possibilities.” Fortunately, the rhinos at the Safari Park can help us do the right thing.