Most people probably think of a zoo veterinarian caring for giraffes, lions, and apes—and of course, we do. But sometimes, our patients are not large or furry.

As a zoo vet, one of the things I really like about my job is that there’s always something new, and there’s always something to continue to learn about. This time, my patient was a fish— an approximately 35-year-old koi at the pond in the San Diego Zoo’s Terrace Garden. It wasn’t my first patient with fins. (Yes, fish get sick sometimes, too!) The veterinary school I attended, at the University of Florida, is one of the very few that includes the study of fish medicine (primarily aquaculture fish). Later, I got plenty of experience in caring for fish during my residency, at the Shedd Aquarium and Brookfield Zoo.

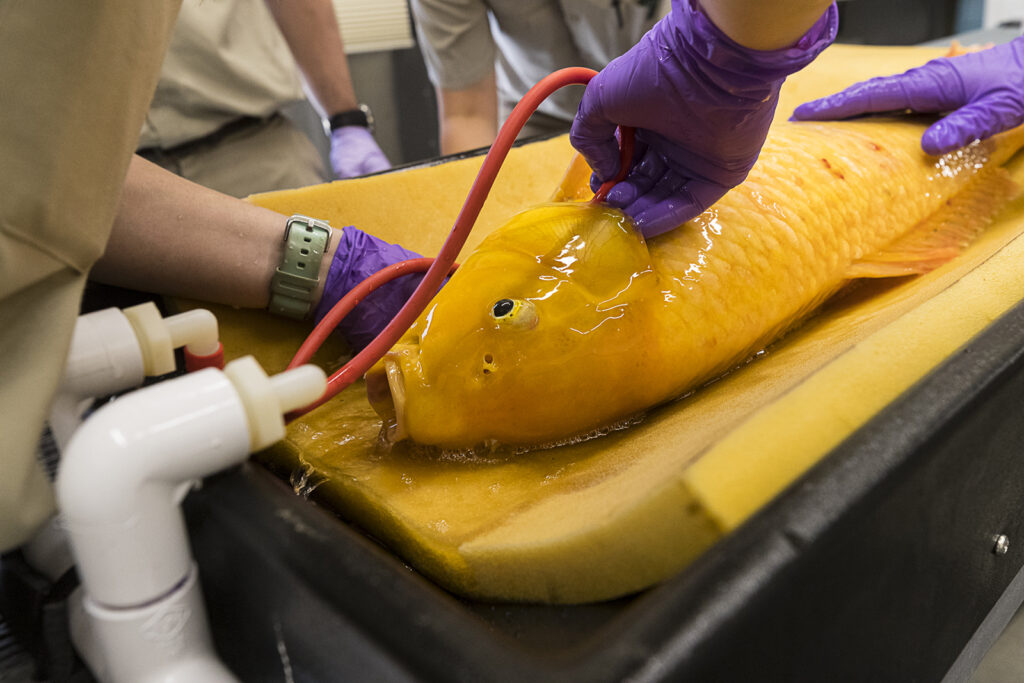

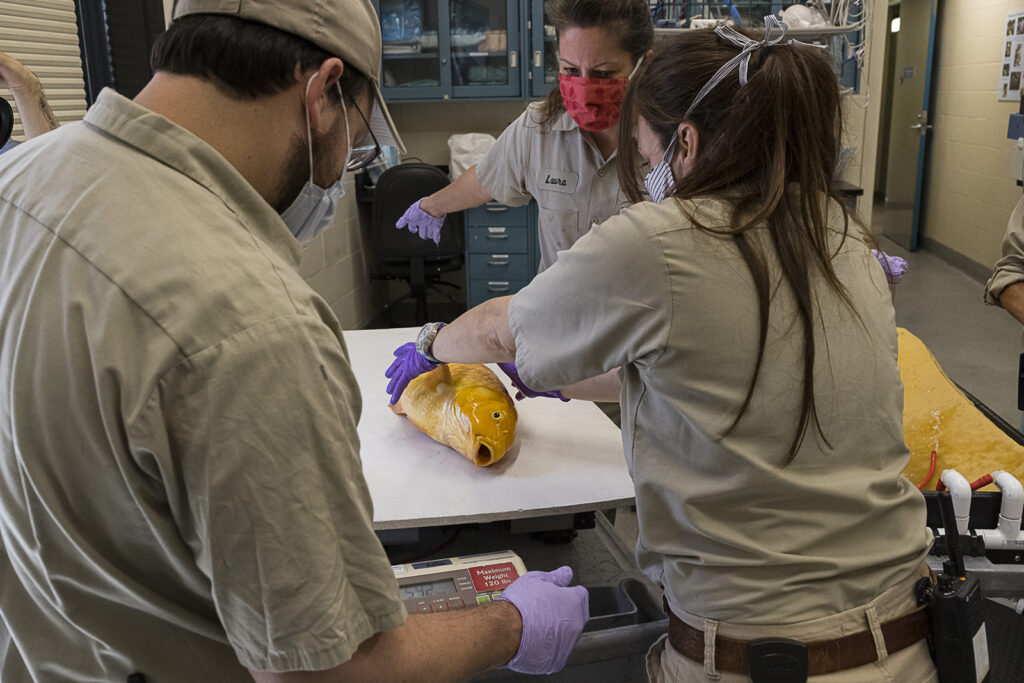

I was called in when wildlife care specialists noticed a skin mass on the fish. Our concern was that the mass could become ulcerated and affect deeper tissue, so they carefully transported the fish to the Zoo’s veterinary hospital, where it we have an exam table that’s just for fish, built by one of our registered veterinary technicians. On this table, we can constantly pump water over a fish’s gills—which is the only way it takes in oxygen—but the rest of the fish’s body is out of water, which allows us to use all of our typical tools for exams and surgery. An anesthetic powder is mixed into the water to immobilize and sedate the patient.

Outside of just doing the procedure, there are other challenges when working with a patient that’s a fish. Chiefly, there is a lot of water around—and a lot of our equipment is electrical. For example, for the surgery itself, I used an electrocautery unit to help cut and coagulate blood vessels. Every challenge has a solution. In this case, to use the unit in water, we adjust it for what’s called “bipolar cautery”—the electrical current passes only through the two ends of forceps we’re using, and it goes no further than in the exact area we’re using it.

With a safe environment in place—for the fish and for us—I was able to remove a total of three skin masses from the koi. Some types of cancer or masses grow deep into the skin or muscle, so I was relieved to see that these masses seemed to affect only the scales in the area and not underlying skin. Our pathologists determined the masses to be a type of skin cancer called spindle cell sarcoma, which is not uncommon in fish. Luckily, this cancer typically doesn’t spread to the rest of the body, but masses can get quite large. Now that we have a diagnosis, we know that we need to continue to monitor those sites for any recurrence.

This surgery reminded me that the variety of species we take care of is always challenging—in a good way, because we don’t get into a routine. We continue to develop our skills and our knowledge base, and learn about the individual animals and the species that we work with.

As for the koi, its surgery sites are healed, and it is back at the shady Terrace Lagoon, swimming in the clean, oxygenated water of its 18,500-gallon pond, and eating normally. Some koi have been known to live more than 200 years, and we hope that this recovered patient has a lot of years ahead of it.

Ben Nevitt is a senior veterinarian for San Diego Zoo Global. Discover more about koi in this article.