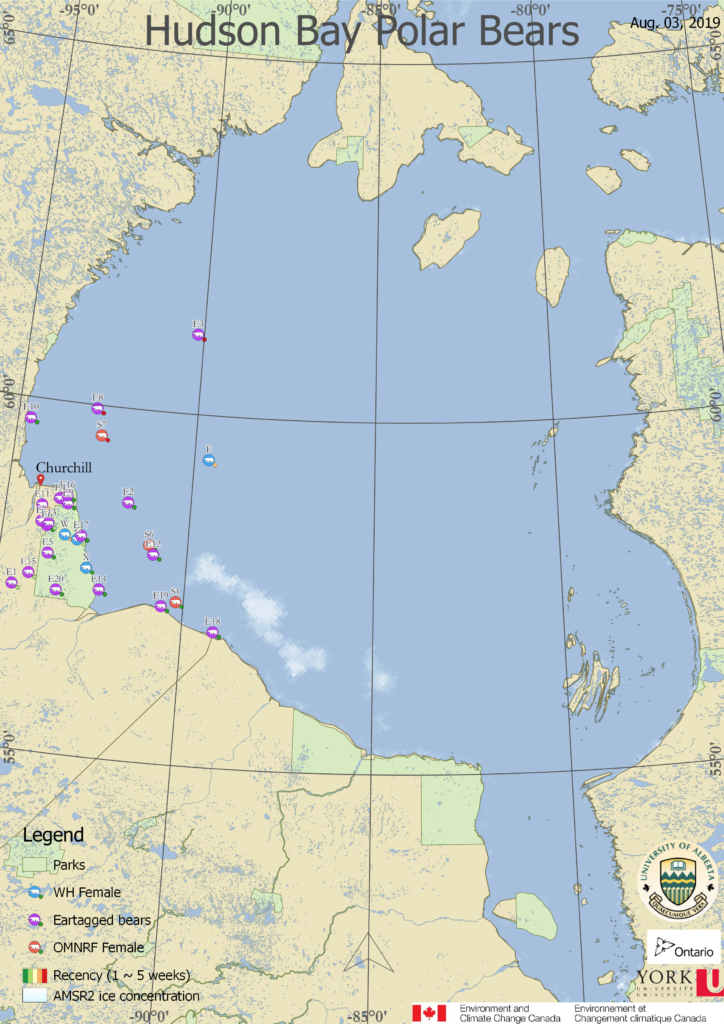

It’s early August, and many people in the northern hemisphere are taking their vacations and enjoying the summer sun, backyard barbecues, and a bit of time away from the daily commute. In the town of Churchill in Manitoba, Canada, it’s also the peak of summer, and temperatures have increased into the high 60s. Plant life is flourishing with long-sunlight days, and wildlife abounds. The sea ice in Hudson Bay has melted—and polar bears are migrating to land.

The polar bear season has started, and the people of Churchill are preparing for another four to five months of living with the largest terrestrial carnivore on the planet. Every year from July through November, polar bears switch from living on the sea ice of Hudson Bay to being on land.

Polar bears that inhabit Hudson Bay have always lived this way. At the southern end of the Arctic ice pack, the seasonal melt in Hudson Bay brings the bears onto land for a summer snooze. Polar bears’ metabolism slows down during the summer. They are coming off their most active time on the spring sea ice, when they were mating and fattening up on seals. Now, it is time for them to lay low on land until the sea ice refreezes.

While these bears may be more relaxed, they are still dangerous. The residents of the town of Churchill take a proactive approach to safety during the polar bear season. Over the years, Churchill has created a strategy—called the Polar Bear Alert Program—that has reduced conflicts between humans and bears. Conservation officers work with residents, and when a marauding polar bear is reported, officers use deterrents to dissuade the bear from coming close to people. Churchill also has a holding facility to give any bears that remain intent on coming to town a “time out.” Polar bear guards accompany visitors to Churchill, serving as experienced eyes and ears to safeguard tourists who may not know what to look for.

The strategy that Churchill uses works—and it is important that it does, as this saves both human and polar bear lives. Programs like these will be ever more necessary across the Arctic in coming years, as rapid warming continues to reduce sea ice and pushes polar bears onto land for longer periods of time.

In cooperation with Churchill, research that I was involved in (“Mass Loss Rates of Fasting Polar Bears,” published in Physiological and Biochemical Zoology: Ecological and Evolutionary Approaches) shows that land has little to offer polar bears, when it comes to wild foods that can sustain them. The longer that polar bears are on land and away from their marine mammal diet, the more likely they will be to search for food that might provide sustenance—and the more likely that they will go toward human settlements to look for it.

Polar bears are part of the very fabric of life in the town of Churchill. As climate change shifts polar bear migratory patterns, the experiences and lessons learned from years of living alongside polar bears will prove invaluable.

Nicholas Pilfold, Ph.D., is a scientist in Population Sustainability at the San Diego Zoo Institute for Conservation Research. Read his previous post, How Cameras Filmed a Rare Black Leopard Mother and Cubs.