Eighty-three filters, hundreds of pumps, and thousands of manual and automated valves. This vital equipment runs the 50 aquatic systems at the San Diego Zoo—from elephant wading pools to the multispecies penguin and shark habitat. Some are heated, some are chilled, and some are at ambient temperature, depending on the species of animal. One thing they have in common is that they all support animal health. The Zoo’s Water Quality department monitors this equipment and the water itself to keep the animals thriving, ensure that water quality is optimal, and maintain water clarity for guests.

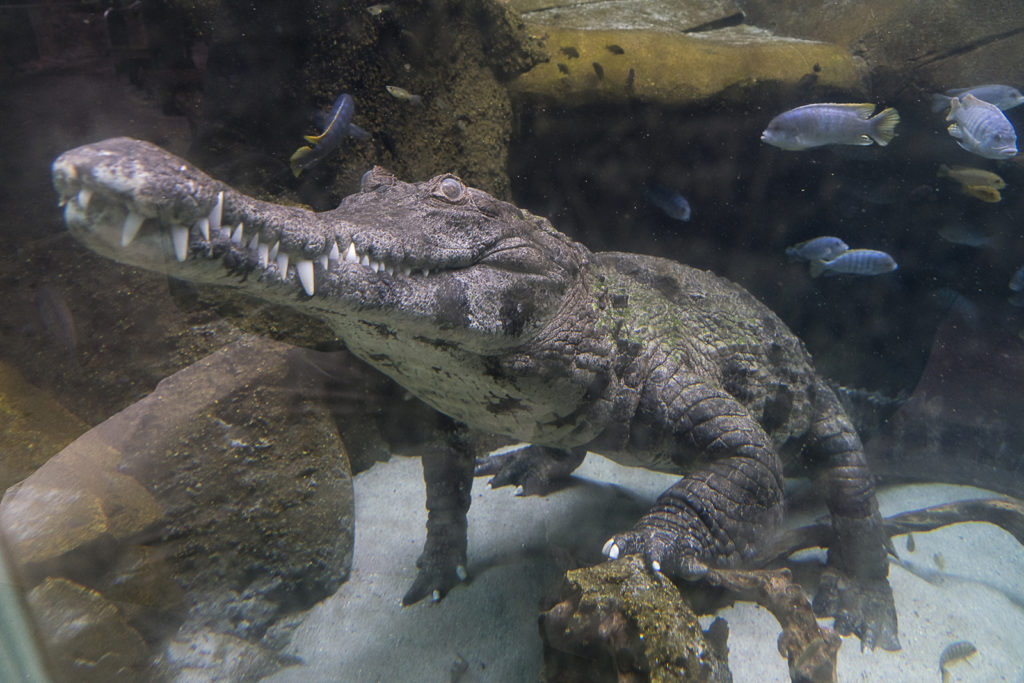

Many mammal, bird, and reptile exhibits include wading or swimming pools. And while exhibiting fish isn’t new to the Zoo (koi have lived in the Terrace Lagoon pool for decades), various fish species—including sharks—are becoming more common in some of our newest animal habitats, like the penguin, dwarf crocodile, and aviary habitats in Africa Rocks. That wouldn’t be possible without the development of life support systems and increased techniques for maintaining water quality. Any pool that supports fish—which live in water and respire with gills—requires mechanical filtration, chemical filtration, and biological filtration.

Mechanical filtration is the process by which particulate matter is removed from the water. This occurs when the water is pumped through sand filters. Regular servicing of the filters is done by reversing the flow of water, and flushing out the compacted particulates. Separate carbon filters do the job of chemical filtration by absorbing organic compounds. An ozone system also functions in chemical filtration, reducing pathogens and breaking down complex organic compounds. Both of these chemical filtration processes consequently “polish” the water for improved clarity for guest viewing.

For fish, the most important type of filtration is biological filtration, which plays a critical role in supporting the nitrogen cycle. This is an ongoing concern, because as animal waste products and uneaten food break down, they release ammonia. Certain bacteria convert ammonia to nitrites, and still other bacteria species convert the nitrites into nitrates—the least toxic form of nitrogen. Without these beneficial bacteria, fish would literally be poisoned by their own waste, so establishing healthy populations of these bacteria is our top priority. Luckily, these hard-working bacteria readily grow on surface areas including grains of sand in the mechanical filters.

Our water quality assistant laboratory technician, Gabriela LaChance, tests water in all the pools regularly, which lets us know how well our filtration processes and equipment are working. In addition to testing for ammonia, nitrites, and nitrates in every aquarium, she collects water samples to analyze pH, dissolved oxygen, salinity, phosphates, and coliform bacteria. While coliforms aren’t a problem for fish, high levels can make mammals—including our human divers—sick. Ozonating the water is an effective way of reducing coliforms in mammal areas like the polar bear pool.

All this monitoring, adjusting, filtering, and backwashing keeps our team quite busy. At the Zoo, this is even more complicated in mixed-species pools like the shark and penguin pool at Africa Rocks. Mammals, reptiles, birds, and fish all have different needs and sensitivities. You might not notice or even see us when you visit, but when you see healthy animals thriving in clear pools, you can be sure we’re on watch, keeping the water clean.

Thad Dirksen is the life support systems manager at the San Diego Zoo.