The price of a movie ticket was $5, Cher’s song Believe was top of the charts, possible Y2K scenarios were bandied about, 9/11 was blissfully unimaginable, and I landed a coveted tour guide gig at the world-famous San Diego Zoo. Life was pretty great!

Then one of the shiniest, if not tiniest, conservation achievements burst onto the scene: the first surviving giant panda cub born outside of China squawked onto the scene on August 21, 1999. Her big, beautiful mother, Bai Yun, gently cradled and nursed the impossibly small cub. A devoted mom from day one, Bai Yun didn’t leave the birth den for three weeks, when she finally zipped outside to get a drink of water. During her brief absence, the San Diego Zoo’s panda team gave the cub a quick health exam. The pink, hairless, Twinkie-sized, Hua Mei (pronounced Whah May), as she came to be known 100 days later, was the first panda cub to survive outside of her native country. San Diego Zoo staff—and people everywhere—were over the moon with the tiny bundle of helpless, squawking joy! She was a beacon of hope for her species. And it was the first time our researchers had a front-row seat to panda maternal care and cub development. Bai Yun’s new daughter also gave rise to the Panda Cam, providing people around the world (with Internet access) the chance to see her grow into her black-and-white glory.

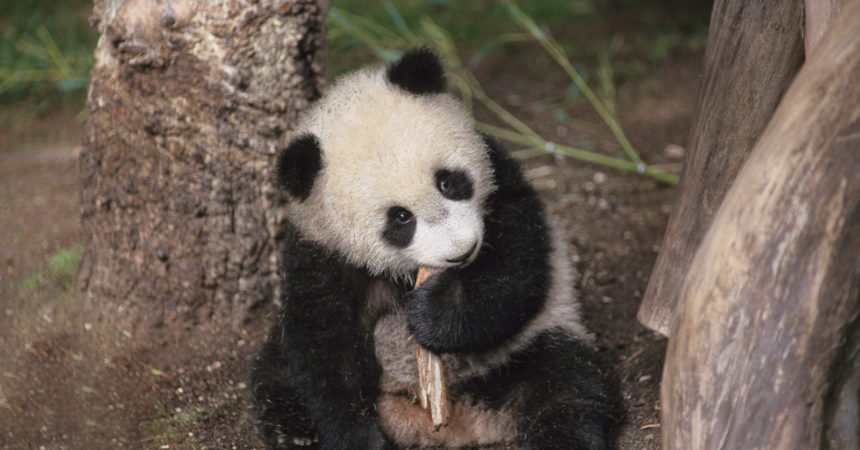

With all the “panda-monium” afoot, I decided to transfer from being a Zoo tour guide to being a panda narrator, once the little one was on exhibit. Thousands of people flocked to the Zoo to get a glimpse of the bears’ roly-poly antics…or even just sleeping in the trees. It’s hard to imagine anything more beguiling than a rotund, toddler-sized, black-and-white bear exploring her world. She was an armful, and weighed as much as a gallon of paint.

While keepers and veterinary staff documented everything that went in and came out of the bears, as a panda narrator, I just got to marvel at Bai Yun’s patience and grace raising her “mini me” in between my panda shifts. One day, “Mei Mei” (as some of us affectionately called her) was mastering how to climb up trees. However, she was still clumsy on the return trip, which lead to a tumble to the ground. My giggles at her intrepid exploration turned to a worried gasp. Fortunately, panda fur is dense and wiry and she all but bounced off of the earth, to everyone’s relief. Hua Mei was a great reason to get to work early, as she was quite spunky and curious, while her mom sat calmly, cracking and devouring bamboo stalks for breakfast.

Back then, panda narrators worked out of a little red research station in front of the panda exhibit (far right corner in the picture above), showing people photos, shellacked scat samples (they look like grassy avocados), a skull and teeth model, and bamboo stalks, which reinforced how strong the bears must be to snap those thick stems like chopsticks. We rattled off panda facts: “they have twins nearly half the time” “only about 12 percent of captive-born pandas survive their first year” “when cubs are born, they’re about the size of a stick of butter” “their biggest threat is habitat loss”, etc. Unlike other animals like raccoons and coyotes that can adapt to living close to and among humans, giant pandas have to stick to their bamboo plan—they need wild mountainous forests of bamboo for food and old growth tree stumps for secure dens to raise their young. I loved talking about pandas!

That Hua Mei went on to bear 10 cubs back in China (she even has a grand-cub now!) and help her species retreat from the abyss of extinction warms my heart. Bai Yun, who had six cubs at the Zoo, taught her offspring well. Giant pandas showed us all that with collaboration, cooperation, shared passion, adequate funding, patience, and a sprinkle of luck, a species can go from dire straits to downlisted (from endangered to vulnerable) in a couple of decades. I am grateful to have had the privilege of basking in the beauty of Bai Yun and her cubs (and Gao Gao!) all these years.

Did you enjoy watching any of Bai Yun’s cubs grow up? Share your memories of the San Diego Zoo pandas over the years (Shi Shi, Gao Gao, Bai Yun, Hua Mei, Mei Sheng, Su Lin, Zhen Zhen, Yun Zi, and Xiao Liwu) in the comments section below. And if you have a Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter account, share your memories and support for pandas using the hashtag #pandas4ever.

Karyl Carmignani is a staff writer for San Diego Zoo Global. Read her previous blog, Virtual Safari Helping Giraffes.